Joseph Nicolar and his Daughters

by Charles Norman Shay as presented at the University of Maine September 25th, 2006.

Pat and CharlesWe are here to-day to discuss the life of Joseph Nicolar, author of “Life & Traditions of the Red Man”, but before we start I would like to bring your attention to a few facts that concern the Penobscot Indians who now reside on a small island in the Penobscot river at Old Town. When the first European settlers set foot on the shores of the so-called “New World” at the beginning of the 1600s, the Penobscot, it was estimated, numbered as many as 50,000 individuals. These numbers were drastically reduced over the years by hunger, a result of the disruption of life of the native people. Wars, between rival factions, which also involved the Native American. Alcoholism brought on as a result of the introduction of alcohol by the settlers. And lastly, diseases, which were prevalent in Europe but did not exist in the “new World”, decimated the region’s Native American population almost to a point of no recovery. As a child I can remember when the total population of our small reservation hovered around 500 individuals.

Pat and CharlesWe are here to-day to discuss the life of Joseph Nicolar, author of “Life & Traditions of the Red Man”, but before we start I would like to bring your attention to a few facts that concern the Penobscot Indians who now reside on a small island in the Penobscot river at Old Town. When the first European settlers set foot on the shores of the so-called “New World” at the beginning of the 1600s, the Penobscot, it was estimated, numbered as many as 50,000 individuals. These numbers were drastically reduced over the years by hunger, a result of the disruption of life of the native people. Wars, between rival factions, which also involved the Native American. Alcoholism brought on as a result of the introduction of alcohol by the settlers. And lastly, diseases, which were prevalent in Europe but did not exist in the “new World”, decimated the region’s Native American population almost to a point of no recovery. As a child I can remember when the total population of our small reservation hovered around 500 individuals.

Although I never knew my grandfather personally (he died almost thirty years before I entered this world), I somehow feel a spiritual connection to him. I recall as a child, a large framed picture of him hanging above the piano in our living room. Trying to gather information I often questioned my mother as to who he was and what he was like as a person. I would now like to share with you a little of what I learned.

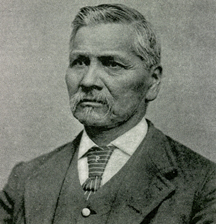

Joseph NicolarJoseph Nicolar was born on the 15th of February 1827, the son of Tomar Nicolar and Mary Malt Neptune and one of six siblings. His mother was the daughter of Lt. Gov. John Neptune, a hereditary chief.

Joseph NicolarJoseph Nicolar was born on the 15th of February 1827, the son of Tomar Nicolar and Mary Malt Neptune and one of six siblings. His mother was the daughter of Lt. Gov. John Neptune, a hereditary chief.

Little is known about Joseph's early childhood, but we do know that his father died when Joseph was only ten years old, making it necessary for him to assume the role of man of the house and to assist in providing for the family. In the year of 1840, twenty years after Maine became a state, his mother wrote a letter to His Excellency the Governor and the Honorable Council of the State of Maine seeking assistance for the education of her son Joseph. Joseph was mainly self-educated up to the age of thirteen, but still with no formal education he was able to read the bible, “pretty well” according to his mother. Research shows that Joseph by his own statements eventually, through the influence of a Mr. Packard, attended school in Rockland and then later in Warren, Brewer and Old Town. It has been said that he probably had the best education of all Penobscot Indians of his time.

With his gift for oration and his hard earned writing skills, he soon began contributing news items and brief articles, in the 1870s, to local newspapers using the initials YS (Young Sabattus) as a signature. Later he wrote articles on tribal arts, crafts and history for an Old Town newspaper.

It is not known when Joseph began his work on The Life & Traditions of the Red Man, but it is assumed to be quite late in his life. The book, of which I have an original first edition copy, was printed in 1893 by C.H. Glass & Company of Bangor, Maine and bound in hard cover, dark green in color. On the spine of the book in gold letters one reads “The Red Man” and just below that “Nicolar”. The frontispiece of the book features a photograph of a very dignified man in a suit with necktie, my grandfather, ‑ the very picture that once hung above the piano in our living room.

Joseph probably had to pay for the publication fees himself so therefore the print-run could not have been very large. Unfortunately, most of the copies of this book were destroyed in a warehouse fire and today very few copies of the original print run are still in existence.

Joseph married Elizabeth Joseph and together they had three daughters. Emma was born in 1868. Lucy was born in 1882 and Florence 1884. Emma, who was housewife and mother to nine children, was in some ways like my mother Florence, very reserved, never uttering a harsh word and a good mother to her children. She and her family were our next-door neighbors and I visited often as a child.

Florence Nicolar Shay at approx. 19yrsFlorence, my mother, was in contrast to her sister Lucy, who I will discuss later, very quiet and reserved. She was an avid piano player, a lover of classical music and a master in the art of basketry. In late 1929, following the stock market crash and the great depression that followed, my parents, who had been living and working in Bristol, Connecticut for the past eight years, were forced to move back to their home on the Indian Reservation at Old Town, Maine for lack of employment in Connecticut. In order to find a way to support their large family they returned to weaving and selling baskets made of brown ash and sweet grass, but the reservation was not the ideal place for such a business because too many of the residents were doing the same thing and as we had no connecting bridge to the main land, visitors and customers were very scarce. It was then that my parents drove up and down the coast looking for the ideal spot to set up a small shop and when they came to Lincolnville Beach on Penobscot Bay they knew immediately that they had found what they were looking for.

Florence Nicolar Shay at approx. 19yrsFlorence, my mother, was in contrast to her sister Lucy, who I will discuss later, very quiet and reserved. She was an avid piano player, a lover of classical music and a master in the art of basketry. In late 1929, following the stock market crash and the great depression that followed, my parents, who had been living and working in Bristol, Connecticut for the past eight years, were forced to move back to their home on the Indian Reservation at Old Town, Maine for lack of employment in Connecticut. In order to find a way to support their large family they returned to weaving and selling baskets made of brown ash and sweet grass, but the reservation was not the ideal place for such a business because too many of the residents were doing the same thing and as we had no connecting bridge to the main land, visitors and customers were very scarce. It was then that my parents drove up and down the coast looking for the ideal spot to set up a small shop and when they came to Lincolnville Beach on Penobscot Bay they knew immediately that they had found what they were looking for.

They were very fortunate in finding a very congenial property owner who had a vacant lot on the main road directly across from the beach and the lobster pound, a restaurant located in the beach area, and he agreed to rent this piece of property to my father at a very reasonable fee. The lobster pound from that era is still in existence today. However, because my parents did not have the finances to construct a wooden building to be used as a small shop, they bought and set up two canvas tents end to end. One was to be used as a sales room and one to be used as living quarters. These were very difficult times for our small family, mother and father with two young boys. At the beginning we had no electricity or water, but fortunately there was a public water pump nearby and we used kerosene for lighting and heat. As business began to pick up my parents were able to rent a small apartment from our landlord and we were able to live more comfortably. My mother died at Lincolnville Beach in May 1960 and my father continued to operate the business until 1966 when he sold out to one of his grandsons who continued to operate the business until the end of the season in 1999. This small business had been in operation for almost seventy years.

During her life, my mother was a strong and active advocate of various legal rights for her people. One of them was the right for parents to send their children to any elementary school in the area of the reservation. A bridge connecting the reservation to the main land and the right to vote in state and federal elections were two other items that were on the agenda of my mother. I do not want to leave you with the impression that my mother was the only advocate of these rights for our native people. This was a joint effort of many of the elders of her time. Although we had our own grade school on the reservation, my mother was of the opinion that too much emphasis was being place on religion and not on an education the would prepare the children for high school and possibly the opportunity to continue on to college or university. Not one to wait to be told what she should do with her own children when it came to their education my mother insisted that I was to attend the public school in Old Town from the first grade on. Being the only Indian boy in a class of over forty children was a difficult time for me, but I soon managed to overcome my shyness and became an accepted classmate and eventually had many friends.

The first bridge, a one-way bridge, was built in November of 1950 and in 1986 was replaced by a spacious two lane bridge, The Penobscot was finally able to travel at will by automobile directly from his front door and we were no longer confined to our little reservation. It was celebrated as a great achievement.

Bruce Poolaw and Lucy Nicolar PoolawLucy was the typical extrovert who enjoyed being in the limelight. This aspect of her character played an important part in her future life. At an early age she took on the stage name of “Princess Watahwaso” and during the 1920s toured the country with Bruce Poolaw, a Kiowa Indian from Oklahoma performing dances and songs of Indian origin and introducing the culture and history of her people to her audience. Lucy and Bruce became man and wife later on in life. Promotional materials for her performances described her as “supreme in the portrayal of Indian Lore and in the interpretation of Indian music”.

Bruce Poolaw and Lucy Nicolar PoolawLucy was the typical extrovert who enjoyed being in the limelight. This aspect of her character played an important part in her future life. At an early age she took on the stage name of “Princess Watahwaso” and during the 1920s toured the country with Bruce Poolaw, a Kiowa Indian from Oklahoma performing dances and songs of Indian origin and introducing the culture and history of her people to her audience. Lucy and Bruce became man and wife later on in life. Promotional materials for her performances described her as “supreme in the portrayal of Indian Lore and in the interpretation of Indian music”.

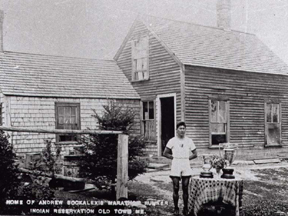

However, Lucy and Bruce also became victims of the stock market crash of 1929 and were forced to return to the Indian Reservation. They bought a choice piece of land and built their home, followed a few years later by a wooden structure that was constructed in the form of a “Teepee”. During the 1930s they continued to be active in show business in the Sate of Maine by visiting tourist resorts and summer camps, putting on exhibitions of Indian songs and dances during the evenings for the entertainment of the guests. In addition, at each of these engagements, they were permitted to erect a small stand where Indian baskets, moccasins and novelties were displayed and sold. As a child I was part of the entertainment team doing my bit as a young Indian dancer – known as “Little Muskrat” thanks to my Aunt Lu. The “Teepee, as mentioned, above was constructed beside their home in 1947 and was used as an Indian novelty shop.

Lucy died in 1969 and her husband Bruce remained on Indian Island for approximately 2 years before returning to his native Oklahoma where he eventually passed on.

In 1988 I came into possession of the property and, after making many necessary repairs, converted the “Teepee” into a small family museum dedicated to my ancestors. The walls and ceiling are covered with murals painted by Calvin Francis, a young and very talented Penobscot artist. The murals depict family members and also various animals that are common to the State of Maine.

Through my research, I now know that my grandfather was a gifted orator, reporter and an elected official of the Penobscots. He held the position of tribal representative to the State Legislature a total of eight times. According to my mother the expertise of both grandparents was often sought to settle disputes and/or to seek advice and assistance with personal problems that sometimes arose involving members of our small community.

In conclusion, I would like to say that Joseph Nicolar became a legend in his own right and that the Penobscots should be very proud of one of their own who persevered at a time when the Native Americans were regarded as unworthy of recognition, regardless of what they had accomplished in life. He was a true inspiration to his people having proved that an education, regardless of how little, was the key to rise above the oppression that was being experienced by Native Americans at the time. Otherwise we were destined to remain second class citizens in our own country the rest of our lives.

Little has been said about Elizabeth Joseph Nicolar, wife to Joseph and the mother to their three daughters. Elizabeth had a very strong influence in the family, especially on her daughters. From their mother they learned the art of basket weaving, the importance of a proper education and that the Native American was entitled to all of the rights that were bestowed to the rest of the citizens of the country. Lizzie, as she was called, was twenty years younger than Joseph. She was described by a local newspaper as being an individual “respected,” intelligent”, and “superior in many ways”. Lizzie traveled throughout New England marketing the baskets produced by herself and her two daughters (Lucy and Florence) and eventually these travels involved sportsman shows that were held in Boston, Chicago and Baltimore. Lizzie was a born leader. She helped found the Wabanaki Club of Indian Island in 1895, which gained membership in the State Federation of Women’s Clubs in 1847 and she was elected its first vice president. Florence, with her sisters Lucy and Emma and sister-in-law Pauline Shay, activated the Women’s Club again in the early 1930s to promote “welfare, education and social progress” for their people and they were once again affiliated with the Maine Federation of Women’s Clubs, as well as with the National Federation. It is very apparent that Joseph and Elizabeth willingly took on the responsibility for the welfare of their people and were able to accomplish very much during their lives, all to the benefit of their family and their people.

Charles Norman ShayComing to a close, I would like to dedicate these words, this short family history that I have just conveyed to you, to my forefathers and, not to forget, my foremothers. I did not find this word in the dictionary but I use it anyway because of the very important role these women played in the lives of their children. They were very active and determined individuals when anything pertaining to the welfare and civil rights of their families was at stake.

Charles Norman ShayComing to a close, I would like to dedicate these words, this short family history that I have just conveyed to you, to my forefathers and, not to forget, my foremothers. I did not find this word in the dictionary but I use it anyway because of the very important role these women played in the lives of their children. They were very active and determined individuals when anything pertaining to the welfare and civil rights of their families was at stake.

I would now like to send a message to them. I will call it “A Spiritual Message of Admiration and Respect for my Ancestors”. I bow my head in a moment of respect to our ancestors, both yours and mine.

Charles Norman Shay (Penobscot)

Chevalier de la Legion d'Honneur

January 11th, 1892 to August 26th, 1919

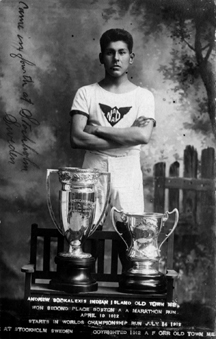

Andrew Sockalexis grew up on Indian Island, Maine. He was ten years old when he started to run. His father had built a track and encouraged Andrew to run. As he grew older, Andrew found other routes and trails to run on. Many times he would run four or five times around an island trail that he trained on. At a very young age, Andrew was determined to become a marathon runner. Andrew ran all throughout the year. In the winter months he would run on the river ice with spiked running shoes and the rest of the year he trained on the numerous trails that spanned his island home. Andrew was timed at thirteen minutes for a trial that was the distance of 2.7 miles.

Andrew Sockalexis grew up on Indian Island, Maine. He was ten years old when he started to run. His father had built a track and encouraged Andrew to run. As he grew older, Andrew found other routes and trails to run on. Many times he would run four or five times around an island trail that he trained on. At a very young age, Andrew was determined to become a marathon runner. Andrew ran all throughout the year. In the winter months he would run on the river ice with spiked running shoes and the rest of the year he trained on the numerous trails that spanned his island home. Andrew was timed at thirteen minutes for a trial that was the distance of 2.7 miles.

As a young man, Andrew had training from Tom Daley of Bangor and Arthur Smith of Orono. Tom Daley trained Andrew until he was 18 years old. In 1911, Arthur Smith, the track coach of the University of Maine, prepared Andrew for the United States Olympic Team tryouts held at Harvard University. He qualified with eleven other runners for the marathon. Andrew participated in the 1912 Olympics hosted by Sweden. The United States marathon team was sponsored by the Dorchester AA team. Andrew was quoted by a newspaper that at all times he was running not only for the United States but also for his own people, the Penobscot. Coach Smith stated to the newspapers that the United States was very confident in their chances of winning the Olympic marathon.

The Boston Post newspaper stated that Andrew was the best hope for a gold medal in the marathon. The strategy for the U.S. team was to hold back in the race and let the 90 degree weather take its toll on the rest of the field of runners. Andrew stated that he waited too long to make his move on the leaders during the race. Andrew finished fourth place with a time of 2:42:07, five minutes behind the winner and only seconds behind the third place finisher. Harold Reynolds, the Boston Post Commissioner, stated that Andrew finished strong and running like the champion he should have been.

The Boston Post newspaper stated that Andrew was the best hope for a gold medal in the marathon. The strategy for the U.S. team was to hold back in the race and let the 90 degree weather take its toll on the rest of the field of runners. Andrew stated that he waited too long to make his move on the leaders during the race. Andrew finished fourth place with a time of 2:42:07, five minutes behind the winner and only seconds behind the third place finisher. Harold Reynolds, the Boston Post Commissioner, stated that Andrew finished strong and running like the champion he should have been.

When Andrew returned home from the Olympics, he received a royal welcome as though he had won the marathon. He was invited to run in many races around New England. Andrew completed the Boston Marathon in 1911 and 1912, finishing second both times. There was hardly a day that went by that Andrew was not running and he never turned down an invitation to run even though many people advised him to take it easy and rest. Andrew just wanted to run and he had run many miles and beat most of the competition.

In 1916, Andrew ran his last race. It was a 15 mile race from Old Town to Bangor. Andrew’s long time friend and Olympic teammate, Clarence DeMar, brought a team from Dorchester, Massachusetts to run against the team that Andrew compiled from Indian Island. Andrew’s team consisted of Sylvester Francis, Arthur Neptune and Everett Ranco. Prior to the race date, Andrew was suffering from a severe cold and complained of chest pains. Against his doctor’s warnings, Andrew insisted on running the race because he did not want disappoint his good friend Clarence, or the fans and his family who attended the race to watch the two Olympians compete again.

Andrew ran with the bad cold and ahead of the field of runners from the start of the race. As they came to the 12 mile marker, Andrew was ahead of his friend Clarence by a couple of hundred yards and was easily going to win the race. Andrew crossed the finish line in Bangor and as he stopped running, he started to cough up blood and collapsed.

Soon after the race, Andrew was diagnosed with Tuberculosis (TB), a disease that had plagued his family. Andrew was very sick for three years and in the summer of 1919, he died in the town of South Paris, Maine. The United States Olympic Committee gave the Sockalexis family a grave monument that read: “A Member of the American Olympic Team at the Fifth Olympiad held in Stockholm, Sweden, July 1912.”

Andrew’s running career was short lived but he had run countless miles during his training and competitions in various races. Andrew was only turning 22 years old when he ran the 1912 Olympic Marathon and the Boston Marathon. At the young age of 27, Andrew had died. His legacy lives on within all the young boys and girls who aspire to run and to those who support the young runners from the Penobscot Nation.

Andrew’s running career was short lived but he had run countless miles during his training and competitions in various races. Andrew was only turning 22 years old when he ran the 1912 Olympic Marathon and the Boston Marathon. At the young age of 27, Andrew had died. His legacy lives on within all the young boys and girls who aspire to run and to those who support the young runners from the Penobscot Nation.

In the 1970’s Michael Sockalexis, a descendant of Andrew, and a fine runner in his own right, began to coach a team from Indian Island. The team, the “Andrew Sockalexis Track Club,” (A.S.T.C.) was active for many years and had some runners who competed on the national level. In the 1980’s the Penobscot Nation honored both Andrew and his cousin Louis, of Professional Baseball fame, by naming the new Ice Arena, the “Sockalexis Ice Arena.” Today the building houses the tribes Bingo operation and still retains the name Sockalexis. In the lobby of the Sockalexis Bingo Palace is a historic display of the athletes Andrew and Louis. Andrew Sockalexis was inducted posthumously in the Maine Sports Hall of Fame in 1984. He was also inducted into the Maine Running Hall of Fame in 1991, and in 2001 he was inducted into the National American Indian Hall of Fame.

In the 1970’s Michael Sockalexis, a descendant of Andrew, and a fine runner in his own right, began to coach a team from Indian Island. The team, the “Andrew Sockalexis Track Club,” (A.S.T.C.) was active for many years and had some runners who competed on the national level. In the 1980’s the Penobscot Nation honored both Andrew and his cousin Louis, of Professional Baseball fame, by naming the new Ice Arena, the “Sockalexis Ice Arena.” Today the building houses the tribes Bingo operation and still retains the name Sockalexis. In the lobby of the Sockalexis Bingo Palace is a historic display of the athletes Andrew and Louis. Andrew Sockalexis was inducted posthumously in the Maine Sports Hall of Fame in 1984. He was also inducted into the Maine Running Hall of Fame in 1991, and in 2001 he was inducted into the National American Indian Hall of Fame.

Joe Attean: More than Thoreau's Guide

Written by S. Glenn Starbird Jr.

One hundred years after the death of Joseph Attean, it is difficult for the historian to understand why his only claim to fame in the eyes of the public is that for a short time he was Henry David Thoreau’s guide.

Attean was far more than an Indian guide. He was the son of a chief, descended from a long line of chiefs. He had the character, qualities and ability needed for the station into which he was born in 1829. The meager records of Penobscot Tribal History which tell us of the troubled times through which he lived gives us brief snatches of his life story but more than that, they tell us of the political factionalism that nearly tore the tribe to pieces. It was finally settled, largely through Attean's efforts and abilities.

A winning team

He worked, as did his fellow tribesmen, in the woods and on the river drives to earn his living, for this was a time when the lives of most Maine men were spent in the woods and on the rivers.

Attean and his nephew Stephen Stanislaus soon gained a reputation for being two of the best river drivers and boatmen on the Penobscot. They normally worked in the same boat, one at the bow and one at the stern and so well did they work together, (they were nearly twins in their height, weight, general looks, manners and mental outlook) that they operated their boat almost as a single man. The fact that Stanislaus was not in the boat the day Joseph Attean died was one factor perhaps more than any other that sealed his fate and that of two others.

Joseph was born Christmas Day, 1829 and grew up during the 1830’s and 1840’s when strong resistance was growing to any of his father’s policies, and those policies of his father’s Lieutenant Governor, John Neptune.

This resistance and political unrest eventually came to a head in 1838 when the group opposed to Attean and Neptune, after consulting with the heads of the Passamaquoddy and Maliseets tribes, (always up to this time federated with the Penobscots) attempted to depose Attean and Neptune and choose new chiefs. Therefore a convention of the three tribes was called to meet at Indian Island Old Town in August 1838 for an election according to ancient custom.

The group opposed to the old chiefs accomplished their purpose and chose new ones but the trouble did not end there for the old leaders refused to step down and their supporters continued to regard them as the true Heads of the Tribe.

Neither party would back down, even rejecting the State’s well-meaning effort at settlement the next year. From that time on those who followed Attean and Neptune were called the Old Party and those favoring the newly-elected leaders Tomer Sockalexis and Attean Orson, the New Party.

The state of affairs continued throughout the 1840’s causing much discord and disruption in the tribal life. Because of this more and more authority of the chiefs was taken over by the State and in several instances political differences resulted in actual bloodshed. When John Hubbard became Governor of Maine he immediately tried to find a way to bring some order out of the chaos that was developing rapidly in both tribes, for a similar situation existed among the Passamaquoddy. In the case of the Passamaquoddy he was successful, with the Penobscots he was not.

Political system shifts

The agreement entered into about 1850 between the officers and principal members of both parties at the urging of the Governor of Maine provided that: “as John Attean and John Neptune were chosen according to the ancient usages of the tribe into their respective offices, that they should remain in said offices during the remainder of their lives, and on the decease of one or both, the vacancy should be filled by majority vote of the male members of the tribe of twenty-one years of age and upwards, in a meeting duly called by the Agent. Said officers to continue for two years, and that an election should be held every year to choose one member of the tribe to represent the tribe before the Legislature and the Governor and Council.”

Elections were then held annually for choice of representative and although the State now recognized Attean and Neptune as the legal chiefs there still existed much ill feelings often resulting in near riot conditions at many elections.

Governor John Attean died in 1858 and after the usual period of mourning the Old Party declared his son Joseph Attean his successor, and he was duly inaugurated by them according to ancient Indian custom, for life.

The succession to the offices of governor and lieutenant governor was still a hotly disputed issue between the two parties but now a generation had passed since the original rupture and it seems apparent that Joseph Attean had decided in his own mind that the time was ripe to settle the chaotic political situation once and for all.

“Good and open-hearted”

Fannie Hardy Eckstorm’s The Penobscot Man (not to be confused with Frank G. Speck’s book of the same title) describes Joseph Attean as “not only brave but good, an open-hearted, patient, forbearing sort of man… loved for his mild justness.” These were exactly the qualities needed in a leader, especially at that particular period.

In addition to his leadership abilities Attean had the prestige of his background and ancestry, and ancestry that traditionally traced to Chief Madockawando and perhaps even further to the half-legendary Bessabez. With these assets Attean commanded respect from even his New Party political opponents. As soon as Attean was firmly in control of his own party he seems to have made enforcement of the agreement of 1850 one of the first issues to be settled.

Attean felt sure of his position and so earnestly did he desire a solution to the tribe’s leadership question that he was willing to submit himself to the elective process for possession of an office that was already his by hereditary right.

Exactly how the fire brands of the two parties were persuaded to submit themselves to the ballot is not known but quite likely Attean’s patience and forbearance played a large part in it. Only one change seems to have been made in the 1850 agreement, that the elections should be annual instead of biennial beginning in 1862. Eckstorm says in The Penobscot Man, “Joseph Attean won his election by popular vote against great opposition, and carried seven out of the eight elections held up to the time of his death. The eighth, by the intervention of the so-called ‘Special Law’ passed by the state to reduce the friction between the parties, was the New Party’s first election, none of Joseph Attean’s party, the Old Party, or Conservatives, voting that year.”

Attean’s popularity even among New Party members did not set too well with New Party leaders, with the result that the Special Law of 1866 was passed giving the two parties exclusive election rights in alternate years beginning in 1867 with the Old Party.

The agreement shows how far Attean was willing to go to settle the party animosity that had almost destroyed the tribe’s political existence. Attean and his new Lieutenant-Governor Saul Neptune (who was chosen by the Old Party to succeed his father John upon the latter’s death in 1865) had little to fear in an open election.

The new law had the desired effect, and from that time on, for the most part elections were conducted in an orderly manner, everyone abiding by the results until the law was again changed about 1930.

Drowned on river drive

Unfortunately, Attean was not to live to see the long term results of his efforts.

Holding political office in the Penobscot Tribe at that period was not the best place to earn a living. Although there was a small stipend, the holder of any office in the tribe could not support a family on it.

In Attean’s case his livelihood involved working in the woods in the winter and on the river drives in the spring and summer. It was while on one of these drives in 1870, near what is now Millinocket, that Attean was drowned in the West Branch of the Penobscot, trying to save the lives of three fellow drivers who could not swim.

Eckstorm has told the story as culled from the memories of the men who were there and saw it happen in her book The Penobscot Man. She said the logs were “ricked up like jackstraws on both sides of the falls.” In one boat was Attean, but on this day his nephew Stanislaus was not with him and this in the end made the difference. In Stanislaus’ place was Charles Prouty, young and inexperienced.

John Ross, the River Boss, later told Eckstorm the responsibility was really his for putting Prouty in the bow position in that boat in the first place.

The boat veered, shot across the thundering current among the jagged rocks on the opposite shore close above the stretch of water known as Blue Rock Pitch. All those who could swim jumped except Attean. Attean dropped his useless pole and grabbed his paddle but the boat would not respond.

Attean stayed with boat

Three non-swimmers clung to the boat, Eckstorm says, “And Joe Attean stayed with them, not clinging as they did, buried in water; not crouching and abject, waiting for the death that faced him, not a coward now, never, but paddle in hand, because the water ran too deep for a pole-hold, standing astride his sunken boat, a big caulked foot upon either gunwhale, working with the last ounce that was in him to drive the sunken wreck and the men clinging to it into some eddy or cleft of the log-jams before they were carried down over the thundering falls.

Attean’s death closed a turbulent era in Penobscot history. His life had been short. But by the time he died in 1870, the political life of the tribe had been given a new lease, largely through his efforts. It had turned in new direction now and was held somewhat in check by the paternalistic power of the state. And it enabled new generations of Penobscots to develop the political skills that would give them an ever-increasing control over their own destiny in the middle half of the coming century.

Mary Alice Nelson Archambaud (Molly Spotted Elk)

In the spotlight on stage the dark-haired dancer twirled, bells tinkling on her ankles and feathers in her hair, as the cheering began and the orchestra drumbeats rose—like thunder from far mountains echoed in chants around bright fires by lakesides, long ago. Suddenly, silence” then applause, bursting like a thundercloud, as the dark-haired dancer bowed; but her eyes seemed far, far away. So “Princess Molly Spotted Elk,” born Mary Alice Nelson on Indian Island, Maine took stages by storm across two continents in the 1920’s and 30’s. Actress, author, poet, dancer, student—and perhaps the first Maine Indian to play a major role in a silent movie—Mary Alice lived many lives and performed for both commoners and kings.

In the spotlight on stage the dark-haired dancer twirled, bells tinkling on her ankles and feathers in her hair, as the cheering began and the orchestra drumbeats rose—like thunder from far mountains echoed in chants around bright fires by lakesides, long ago. Suddenly, silence” then applause, bursting like a thundercloud, as the dark-haired dancer bowed; but her eyes seemed far, far away. So “Princess Molly Spotted Elk,” born Mary Alice Nelson on Indian Island, Maine took stages by storm across two continents in the 1920’s and 30’s. Actress, author, poet, dancer, student—and perhaps the first Maine Indian to play a major role in a silent movie—Mary Alice lived many lives and performed for both commoners and kings.

“She was a remarkable person in any light,” says the former director of the Penobscot Nation Museum, “and led, I think, one of the most amazing unknown lives of any modern American women.”

One of life’s free spirits, she paid a sad price for living. A world traveler, her story began and ended where her heart always lived, on Indian Island.

Born on Indian Island, near Old Town, on November 17, 1903, Mary Alice (in Penobscot Molly Dellis) was the first child of Philomena Solis Nelson and Horace Nelson, a future governor/chief of the Penobscot Nation. Her family had a rich heritage” Molly’s mother was one of the best basket makers of her day, her father was the first Penobscot to attend Dartmouth College, and her grandfathers, both maternal and paternal, had been leaders of their tribes. Her mother’s father was a chief of a Canadian Maliseet Tribe, he was adopted by the Maliseet Solis family but was of Penobscot 'Bear' Mitchell lineage, and her father’s father, Peter Nelson, was the vice-chief, then Lt. Governor, of the Penobscot Nation.

Molly was the eldest child and she helped raise her seven younger brothers and sisters. All were unique individuals. Her sister, Eunice, was later the first Penobscot to earn a Ph.D. Molly, most of all, took to learning traditional dances at age thirteen to help support her family, and she would ask tribal elders about the wide world. Her family always smiled at the saying “curiosity killed the cat,” which was tailor-made for Molly.

Her ambition matched her beauty, and after graduating from Old Town High School, Molly attended the University of Pennsylvania for two years, studying anthropology by day and scrubbing floors by night. Her interests were as wide as the world—archaeology, geology, ethnology, and all things Aztec, Mayan, and the Native American groups. As an eager undergraduate, she contributed to Dr. Frank Gouldsmith Speck’s study of her tribe, Penobscot Man: The Life of a Forest Tribe in Maine.

When her money gave out, undaunted, Molly turned to her beloved native dancing for a living, crisscrossing the country during Prohibition days in the vaudeville troupe of the famous Tex ("Hello, suckers!") Guinan. Stints soon followed at the Schubert Theater and the Provincetown Players, where Eugene O’Neill’s early players were produced. Performing now as "Molly Spotted Elk," she wrote her own music, made her own costumes and was a sensation everywhere-even dancing topless sometimes, her family remembers, "A happy and completely free spirit."

In 1928, her friendship with a Hollywood producer won Molly Spotted Elk the lead in a Paramount movie, "The Silent Enemy." Inspired by an actual New York Museum of Natural History expedition and filmed in northern Ontario, using an all-Indian cast and authentic Indian costumes, tools and customs, the film followed an Ojibway Indian tribe's struggle against a silent enemy-hunger-before the coming of the white man. For over a year Molly endured the Canadian cold and weather playing the central role of "Neewa," the tribal chief's daughter.

Released in 1930, "The Silent Enemy" was one of Paramount's very last silent films. Perhaps because it broke stereotypes-or was out of step with the Jazz Age-it was not a success, and "Silent Enemy" vanished into Paramount's vaults to lie forgotten for 40 years. With it went Molly Spotted Elk's career as a star.

Hollywood's loss was Europe's gain. In 1931, Molly sailed for France as the American Indian representative in the ballet corps of the International Colonial Exposition. Following her recital of native dances at Fontainbleau's Conservatory of Music, she struck out across the continent, where the Penobscot governor's daughter danced before old World royalty, including King Alphonso of Spain.

Back again briefly in America, Molly appeared as an extra in several Hollywood classics-including "Last of the Mohicans" (1936), "The Charge of the Light Brigade"(Warner Brothers, 1936), "The Good Earth" (MGM, 1937), and "Lost Horizon"(Columbia, 1936)-but her heart remained in Europe. Settling in Paris' colorful artist's colony, Molly relished the role of a vibrant American émigré, She studied at the Sorbonne, dug in dusty archives for documents about France's first contact with the Penobscots, taught ballet and caught the eye of journalist John Stephen Frederic Archambaud.

"He was just crazy about American cowboys and Indians" remembers their daughter, Jean. "He begged for an opportunity to interview her. Well, they met and they married."

Jean Archambaud was the only child of their "very spiritual and sadly short marriage. When World War II burst over Europe, Archambaud, a political journalist for Le Paris Soir, was Red Cross Relief Director near Bordeaux, and an outspoken anti-Nazi. After France fell to the Nazis in 1940, he vanished, and Molly and her 6-year-old daughter fled on foot over the Pyrenees Mountains into Portugal.

"We walked, we ran, we rode ambulances," Jean recalls. "A newsman picked us up once, and my mother always claimed it was Howard K. Smith. Adventure always followed her even in adversity."

On their coming to the United States, their ship cabin was ransacked and searched. Even after the war ended Molly never could find any final word about her husband's fate.

Sorrow followed her home to Indian Island, where she arrived in July 1940, but then went to New York City and continued performing, returning to Indian Island for good in the early 1950's. Molly's only grandson John, named in memory of her husband, inherited much of her adventurous spirit. In 1973, he bravely carried medicine between the armed camps when the FBI and the American Indian Movement, (AIM) squared off during the Indian occupation of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, the site of the 1891 United State Army massacre that ended the Plains Indian Wars. In 1974, he returned to Lincoln, Nebraska, to serve as a witness in the Federal trials that followed and was killed under mysterious circumstances. His death, too, was never resolved.

"He lived with Molly, and she loved him dearly," recalls Jean. "To this day, nothing adds up right. An artist to the end, in her old age Molly crafted Indian dolls in traditional dress, some of which are now in the Smithsonian. She wrote constantly-children's stories based on Penobscot legends, a translation of Penobscot into English and French-and saved reams of diaries, notes, and a lifetime of letters. In recent years a copy of "The Silent Enemy," was rescued from deterioration in Paramount's vaults and has enjoyed a revival in anthropology classes at Vassar and other American colleges Penobscot youth may now see a copy of the film at the Penobscot Nation Museum on Indian Island. "I was so caught up in the experiences of seeing my mother--so young again," her daughter Jean smiles. She sought learning all her life, and now it's a teaching tool, I think she'd like that." Molly Spotted Elk, the dark-eyed dancer who once delighted audiences around the world, died on Indian Island February 21, 1977, at the age of 73. In 1986, Molly became a charter member of the Native American Hall of Honor in Page, Arizona, there joining Louis Sockalexis and Joseph Attean to present the proud Penobscot Nation. "Molly Spotted Elk's life made a full circle," reads her charter certificate. "It was trail of tears." Molly's life has been the subject of numerous interviews in Maine newspapers. But Spotted Elk's story has now been captured in full in Bunny McBride's Molly Spotted Elk: A Penobscot in Paris (University of Oklahoma Press, 1995).A journalist and Columbia University-trained anthropologist, McBride recreates the details of Spotted Elk's life in a rich and inviting prose born of Spotted Elk's own diaries.

The Saturday Evening Post lauded Spotted Elk and "The Silent Enemy" as deserving of a Pulitzer Prize as "the best American dramatic creation for the year 1930" -- and in an ironic fulfillment of that commendation, McBride's book has been nominated for the Pulitzer Prize for biography. It is worthy of that and more. Accessible to the young reader, detailed enough for the scholar of Indian history, "Molly Spotted Elk" is an enjoyable book to read.

Today Molly Spotted Elks writings exist in a book published by the Maine Folklife Center. The book, by author Molly Spotted Elk, is titled: Katahdin: Wigwam’s Tales of the Abnaki Tribe, is part of the Northeast Folklore Series.

Henry David Thoreau had a lifelong interest in Native American Cultures. As a youth his eyes scanned the ground for small stone fragments left by, what he saw as, vanishing cultures. When Thoreau first visited Indian Island, the home of the Penobscot Nation, he penned the following description: “The ferry here took us past the Indian island. As we left the shore, I observed a short shabby washerwoman-looking Indian; they commonly have the woebegone look of the girl that cried for spilt milk… This picture will do to put before the Indian’s history, that is, the history of his extinction.” Thoreau, like others of his era, believed that Native American culture was on the decline. He was disappointed with what remained of the Penobscot community he witnessed in 1846: “Politics are all the rage with them now. I even thought a row of wigwams, with a dance of pow-wows, and a prisoner tortured at the stake, would be more respectable than this.” In his eyes Penobscot were losing that romantic image of the “noble savage” and exchanging it for politics. His image of the Indian man was not yet realized beyond this stereotypical view.

On Thoreau’s 1846 journey, he aspired to climb Katahdin. He tried to hire Louis Neptune and another man on Mattanawcook Island near Lincoln, but they were unable to get together at the appointed destination. Thoreau described Neptune as “a small, wiry man, with puckered and wrinkled face, yet he seemed the chief man of the two…” Thoreau settled for a couple of non-Native American woodsmen to guide him up the West Branch of the Penobscot River. He later wrote, “We were lucky to have exchanged our Indians, whom we did not know, for these men, who… were reputed the best boat men on the river… and the Indian is said not to be so skillful in the management of the bateau. He is, for the most part, less to be relied on, and more disposed to sulks and whims.” It was not until his next trip that Thoreau actually had more than a conversation with a Penobscot Indian and a better understanding of Penobscots.

On the second journey Thoreau hired the skills of Joseph Attean: “He was a good looking Indian, twenty-four years old, apparently of unmixed blood, short and stout, with a broad face and reddish complexion, and eyes, methinks, narrower and more turned up at the outer corners than ours, answering to the description of his race. Besides his under clothing, he wore a red flannel shirt, woolen pants, and a black Kossuth hat, the ordinary dress of the lumberman, and, to a considerable extent, of the Penobscot Indian.” This description was from the first meeting with Attean at Moosehead Lake. Thoreau did not have a chance to meet Attean on the stagecoach because Attean gave up his seat for ladies, riding in the rain on the outside of the stage. Thoreau’s description of Attean remained largely stereotypical. However, on this trip Thoreau’s overall assumptions of Native American culture was lessened by Attean’s presence. Thoreau needed to look beyond the “Indian” actions to see the truly great Penobscot man.

On Thoreau’s final journey, he hired Joe Polis. It appeared that the more contact Thoreau had with Penobscot Guides, the more he saw them as men and not just “Indians.” Thoreau’s fascination for Native Americans never wavered. In his later years he worked on a comprehensive book about Native Americans. His journeys to the Maine woods with Attean and Polis changed his perceptions of what it meant to be Native American in a rapidly changing world.

One of Thoreau’s biggest contributions to Penobscot history was the documentation of Penobscot place names. These names indicate how Penobscot ancestors saw the landscape. Thoreau once wrote in his journals that “the Indian language reveals another wholly new life to us.” By having contact with two Penobscot men, Thoreau discovered a new, more informed view of Native Americans, moving from his naïve assumption to an understanding that included respect and reverence. Reportedly on his death bed Thoreau's final words were: “Moose” and “Indian.”